MIN visited seven boat businesses in Lombardy – the region surrounding Milan, Italy, to find out about the DNA and texture of Italian family enterprises.

“Family companies are like wild horses to ride – they have huge potential,” says Alberto Osculati (executive director for the distribution and accessory manufacturing company). Within Osculati’s sprawling industrial complex which spans 21,000 square metres, the company employs 160 plus people, three siblings and their father (industriously leafing through papers and simultaneously tapping on his calculator while ignoring the busy office chatter).

Between them all, they produce 7,000 marine accessory products, distribute around 20,000 and print what’s arguably the biggest doorstep of a catalogue at nearly 1,200 pages.

As Osculati noted in an interview this summer with MIN, it is an extremely difficult time for marine businesses, but he’s feeling confident that systems and changes already in place will steer the Italian firm.

“In our situation with three of us, plus my father working together, we have different abilities that complement each other,” says Alberto Osculati (pictured middle).

Family dynamics play a huge part in how many Italian businesses are run. While the diversity of family members is potentially very good, it can be complex to manage.

“I take a long-term view, while my brother [George] is very practical.

I share my vision with him and he shares with me the problems to applying my vision in our current reality.”

Osculati explains that he considers himself the “two and a half” generation.

“My grandfather started a shop, but my father built the company between the 1970s and 2000, and in the last 25 years, my siblings and I have grown it further.”

That all family members are inputting into the company is evident. They’re all yacht owners and they’re all invested in development. For example, the design team’s currently working on widening a step after the oldest Osculati mentioned his boat’s access could be improved.

That so many Italian family-owned businesses are still designing, manufacturing and producing product is put down to several factors.

One of those is the post WW2-context. In 1948 the Marshall Plan significantly aided Italy’s post war recovery by providing substantial aid for reconstruction, modernisation, and economic development. The aid focused on infrastructure, industry, and agriculture, and helped Italian boatbuilders develop their industry.

“A lot of companies were built in the 50s or early 60s,” explains Osculati. “They were built by a first generation, and now this generation is passing the same company to its own heirs.”

But there is more at play than that. Osculati notes that there’s financing challenges, “In Italy most companies have self-financed because the financing market is not working as well as in northern Europe or in the US,” and this means that “companies have to find their own way of financing instead of a company growing in a structured way.”

Thus, boat businesses in Lombardy (and Italy as a whole) may grow slowly and cautiously, relying on internal capital.

Plus, he says, doing business in Italy is very complicated. “Sometimes family companies can adapt more easily to the complexity,” and that’s why they survive.

“The main problem in Italy is the justice system, you don’t have clarity. I’m not talking about criminal offences, I’m talking about business problems: a land problem, a hiring problem, a problem with the workers, something like that,” he adds.

“You may have to go to court but the answer will only come after five years.”

Another factor for keeping it in the family is that, as Osculati says, “the system in Italy is very, very rigid.”

If a company employs 15 people or more, “you cannot substantially fire anybody.” And this means companies stay below fifteen people so it’s easier to find, hire and change workers.

Italy: a market of family-owned businesses for the future

“This area, Lombardy, has always been family business oriented,” says Gianni Zucco, co-founder of HP Watermakers, which has 14 employees. The company makes a wide range of complete onboard water treatment packages, and Zucco’s dad can be found busily assembling parts in the depths of the 3,000 square metre facility alongside the rest of the team.

The majority of components are produced in-house. Gianni Zucco revealed more of the company’s strategies in an interview with MIN earlier this year.

Zucco believes that Italy is a hot bed of micro companies that specialise in doing small things for big assemblies. Many of those are in the fourth generation, and he expects there to be a fifth and sixth.

“Maybe it’s part of our culture, our DNA. We are a micro company, but we act like a corporation.”

The company recently celebrated its 30th year in business.

“The structure of families has always helped the growth of this kind of family business. [In Italy] we don’t leave the family when we’re 18, we stick together and have the same targets. If something is created, normally it’s never abandoned.

“We don’t give away businesses to corporations, even though being company owners in this country or in Europe is very difficult due to overwhelming tax levels.

“We work from January to September just to pay taxes, and from September to December to make our money.”

Zucco says that it’s a cultural thing, one that people from different backgrounds might not readily understand. He says he’s not building the company for the money, but it’s a passion.

“If I would do this for money, I wouldn’t do it. Maybe I’m naive. But I’m sure that my next generation is following [in my footsteps].”

The word passion comes up regularly for the boat businesses in Lombardy.

“Family businesses aren’t about Excel sheets, they’re about passion,” says Andrea Gallinea of marine product producer, Gallinea. His sister might not agree, she’s the company accountant. “She saves money, I spend it,” he laughs.

“With family-owned businesses, passion is part of the deal. Family businesses can decide to invest and cover costs. There are many opportunities for small companies if you are lucky, and have good partnerships between people inside the company,” he says.

The company specialises in marine equipment and makes a range of products related to boat windshield wipers, fans, and marine automation systems.

Gallinea describes the ethos of his company as being to “move what we can.” He’s all about motion, from windshield wipers to lift mechanisms. “If a shipyard has something to move, we say ‘yes’.”

But the request has to come from a third party. “We don’t speak directly with end customers; we work with OEMs, shipyards, or distributors who handle private clients,” he says.

Currently the company’s working with Nautys on boat furniture which… moves. Gallinea says the integrated electromechanical movements are perfect for optimising space onboard.

“It’s a range of outdoor furniture for boats and homes. This collaboration is with a Korean company that has headquarters in Italy.

“From our perspective, this product line is extremely innovative. The tables can move up and down, have wireless phone charging capabilities, and emit sounds like speakers,” he says with passion.

But passion can be followed by pressure to keep it going, although Giacomo Castoldi, the current owner of Castoldi, says he has it all under control.

“I’ve always had this pressure,” he says. “I guess my father had this pressure from his father and so on. I don’t feel that pressure because I’m surrounded by skilled people.”

Castoldi makes both tenders and waterjet propulsion systems and was started by Giacomo Castoldi’s grandfather. The original business idea has evolved meeting the market and investing a lot in research and development, especially in the waterjet side.

Visiting the 18,000 square metre immense site with its 98 employees is like being immersed in two different companies, one creating tenders, the other creating what goes in them – the former was actually established to service the latter. It’s a spectacular sight to see the progress of the 50 or so tenders a year which roll out the doors.

The pride of succession

Castoldi says that both tenders and water jets are very demanding markets with competitors.

“If you want to keep the company alive and kicking, you have to invest in R&D and always come out with new ideas. I was taught this by my father and grandfather, and I try to keep the same course,” he adds.

Aside from the product developments (Castoldi’s launching a new limousine in 2025), he does feel the pressure of having his name . . . everywhere.

“When you have your name on the product, you are responsible for it. People know that you are responsible. A lot of people call me because they know I take care of our customers. I want the product to be as good as possible – this is the idea of a family business.”

Italian descendants take deep personal pride in their companies, often seeing them as legacies to pass on rather than assets to sell. So transitioning leadership must be a sensitive but vital process for the boat businesses in Lombardy and beyond.

Handing over leadership is complex; some successors are hesitant or unsure. Others embrace the role

but feel the weight of tradition.

One company which is currently embarking on that process is Foresti & Suardi. It makes accessories – stunning bowls and door handles and more – with its manufacturing facilities split from its main offices, but still in the area of Predore, Lake Iseo. It develops roughly five to ten new items per year.

“Every detail is taken into consideration, we need more time for that, so there are fewer products,” says Luciano Paissoni, owner.

Paissoni is gradually offering his son the ropes. “I love my job, I want to be involved, I cannot see myself not coming to the office. But on the other side I am delegating more and more,” Paissoni says.

Three years ago, Paissoni senior had to make a decision about the future of the company. After an equity fund made two approaches to buy the business, Paissoni asked his son, Luca, what he wanted him to do.

Luca said he’d quit football to join the company. (He was a midfielder for ASD Montorfano Rovato.)

The decision proved beneficial, as evidenced by Foresti & Suardi’s continued success three years later.

The company, established in 1961, currently employs 70 people, with five family members actively involved in the business across three generations.

Shipyard buy outs change business relations

But not all companies can stay in the bloodline. Italy’s shipbuilding dynasties have moved on from family ownership. That evolution has meant a meaningful change to doing business as relationships with shipyards and clients used to be family-to-family; now many shipyards are investor-owned, shifting dynamics toward transactional models.

Fiorella Besenzoni – from Besenzoni luxury yacht solutions – says that her company’s relationship with shipyards changed about 15 years ago, when the structure of the shipyards changed.

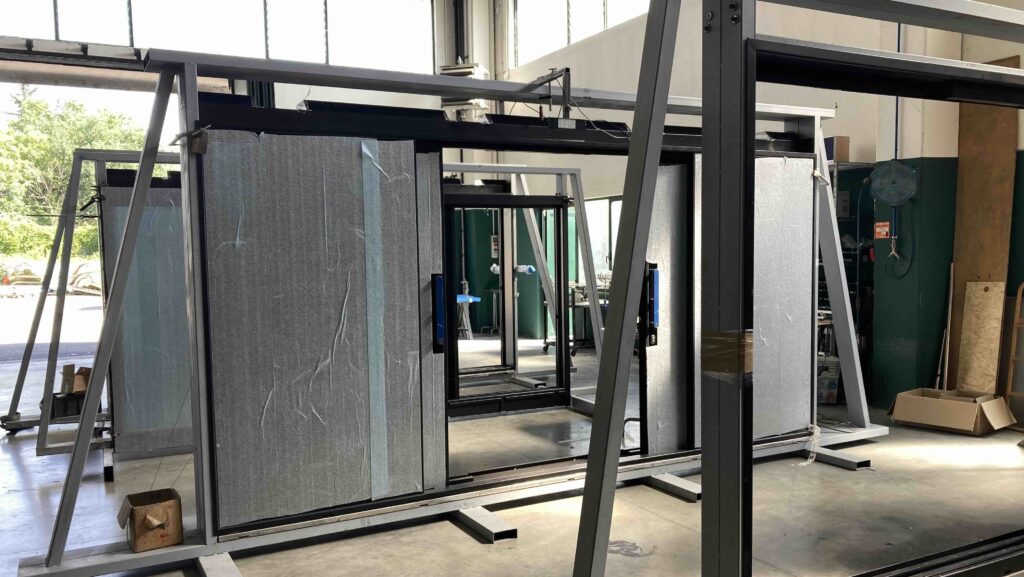

“In Italy, for example (in England as well) shipyards were a family business, like ours,” she says from the company’s plant-covered headquarters which is tucked away in a residential street but then opens like a Tardis over 20,000 square metres.

From its facility, Besenzoni designs and manufactures high-end components and accessories for yachts and superyachts, including gangways, cranes, helm seats, and ladders.

“But now the shipyards are owned by funds or they are companies with managers … But we are used to it, but it’s different, of course.”

She says that her father was “obsessed with quality and safety,” and that has been carried over into everything that the company now does. Besenzoni calls it a family business, but a ‘complex’ one.

At the end of the day, for any business to be successful, it needs complementary skill sets. And that’s what Marco Donà, CEO of Saim, says he has with his siblings. He describes the situation as ‘perfect’, although that wasn’t “a given at the start because we are so different from each other.

“My brother and I are like chalk and cheese, but we found out we complement each other. I have more of a sales and marketing attitude, while he’s more analytical and finance-oriented, which is just perfect.” (Donà’s brother takes care of the industrial business.)

“We found a way to work together without fighting, something that was impossible when we were kids. My sister [who looks after the shows and catalogues] is close to me and has always been, so I love working with her . . . she takes care of me.”

Saim Marine manufactures, imports and distributes high-tech components to shipyards from its 9,000 square metre facilities (it has circa 100 employees) and also provides support for project development. Serving recreational and commercial clients, it has a direct service network along the coasts of Italy, France, Slovenia, Croatia, and internationally. The network includes 90 service dealers, and 26 parts dealers.

The post Industry spotlight: Italian family manufacturers build their brands and core markets appeared first on Marine Industry News.

Leave a Reply