According to a new scientific study, warheads left over from World War II are busily supporting life underneath the water.

About 1.6 million tons of munitions are estimated to be dumped around Germany’s coastlines – most dumping happened during the demilitarisation after World War II, says the study in published in Communications earth and environment.

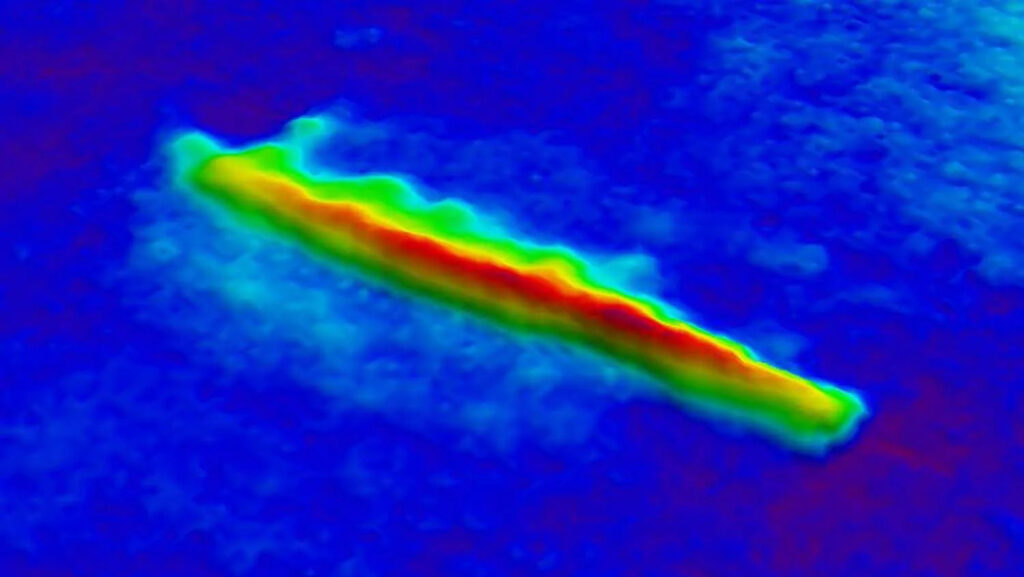

Now a team of researchers have discovered and investigated one dumpsite located in the northern part of the Lübeck Bay. Within the area – practically teaming with epifauna – were a total of 12 objects. Those objects (large metal cylinders 130–140 cm long and 90–100 cm in diameter) are thought to be flying bomb warheads. While some of them were almost intact, others were rusted out with the explosive content strongly dissolved.

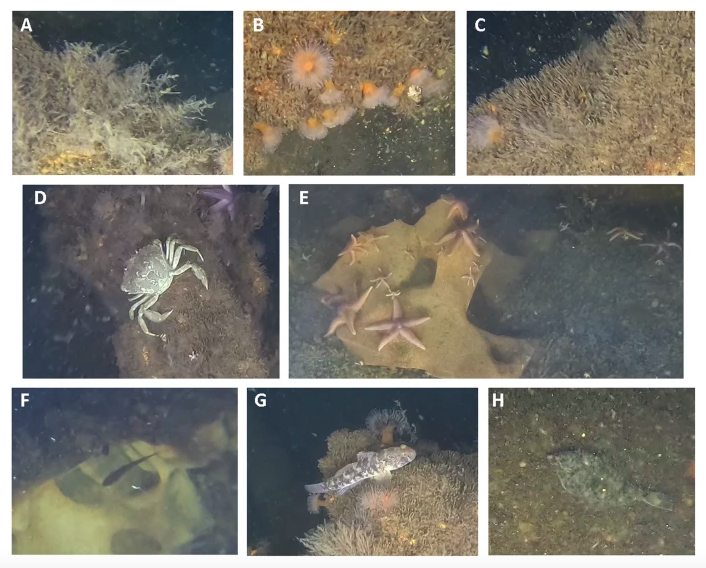

In October 2024 the team sent a remotely operated vehicle with two camera systems onboard to help the scientists visually identify and count epifauna species, living on and around the munition and in the surrounding area. Epifauna refers to animals that live on, or are attached to, the seafloor or submerged objects with examples including corals, mussels, barnacles, echinoderms, and sponges.

Despite the potential negative effects of the toxic munition compounds, images have previously shown dense populations of algae, hydroids, mussels, and other epifauna on munition, including mines, torpedo heads, bombs, and wooden crates. This latest research was to help establish the composition and structure of the epifaunal communities.

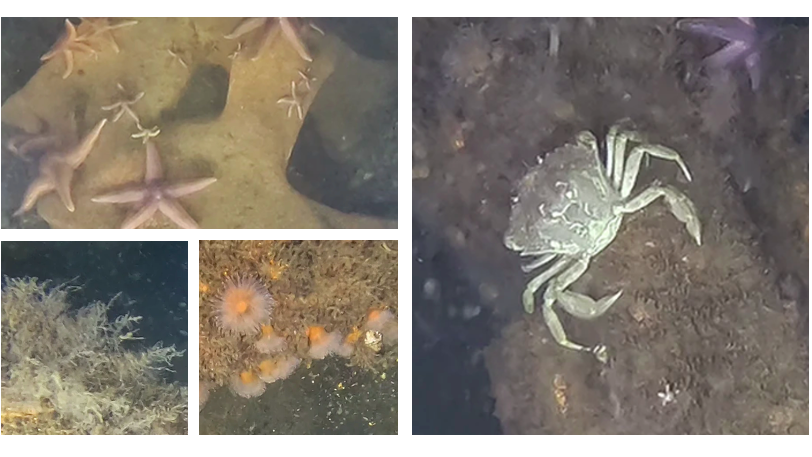

In this study, eight species were identified as living on the human-made substrate. Five of those were invertebrate epifauna and three were fish species. Scientist report seeing anemones and starfish. During close observations, the polychaetes (Polydora ciliata, identifiable by tubes – see image C below) dominated, reaching over 90 per cent of the total abundance.

Starfish and crabs crawl on explosives

The team found that the majority of epifauna was found on metal carcasses, while the exposed explosive was usually free of visible overgrowth. On rare occasions, individual starfish Asterias rubens or crabs Carcinus maenas were seen crawling on the surface of the explosive, or smaller Polydora ciliata colonies developed in crevices filled with sediment.

Mussels exposed to TNT concentrations above 0.6 mg/L tended to keep their shells closed, interfering with normal filtering behaviour.

“We were prepared to see significantly lower numbers of all kinds of animals,” study author Andrey Vedenin with the Senckenberg Research Institute in Germany told the AP. “But it turned out the opposite.”

There are a lot of published studies on other kinds of artificial hard substrata, says the team, like ones on shipwrecks, offshore wind farms, oil rigs, pipe-lines, and concrete bases for future coral reefs etc. Both natural and artificial hard substrata are known to provide living space and attract species, like algae, invertebrates, and fish.

Now the team can say with confidence that individual munition objects, and piles of munition items, also drive faunal abundance. And that diversity spreads up to several meters around each munition object.

Controversial results: nature versus man-made

But comparisons of natural hard substrata (stones and boulders) with artificial ones show controversial results. That’s because sometimes artificial structures provide higher epifaunal abundance and diversity.

The factors that matter with epifauna abundance and diversity include the surface of the substrate, its material, and shape. Unsurprisingly, recently submerged artificial structures usually show lower abundance and diversity compared to natural substrata, which have been present in the area for hundreds or thousands of years.

A Campanulariidae gen.sp.; B Metridium dianthus; C Polydora ciliata; D Carcinus maenas; E Asterias rubens; F Gadus morrhua; G Gobius niger; H Platichthys flesus.

The post World War II explosives provide home for thriving marine life appeared first on Marine Industry News.

Leave a Reply